Education can be described as a public good required for the transition of a child throughout life. This is sufficient for the promulgation of several international laws and global campaigns recognizing it as a basic human right for all. Among the international laws are the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights, the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (Global Campaign for Education, n.d.). The global education campaigns include the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and Education for All (EFA).

The global education agenda, which is the focus of this article, is more or less a broad coalition of national heads, international organizations, bi-lateral agencies, civil society groups, and development agencies (such as the World Bank, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) aimed at bringing about transformative outcomes in the education sector) (Dakar Framework for Action, 2000). This is evident in goal four of the Sustainable Development Agenda, “to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all,” which remains the impetus behind the other sixteen SDGs and instrumental in preparing the populace for changing society (Williams and Ginsburg, 2012, 3). The 2030 global education agenda stresses quality education as a common good in a learning society, in which knowledge shared in higher institutions should transcend innovations, peaceful coexistence, employability, and solutions for communities. It further recognizes equitable access and guards against a new source of power subsumed in inequalities and divides among the countries in the world (Williams and Ginsburg, 2012, 3).

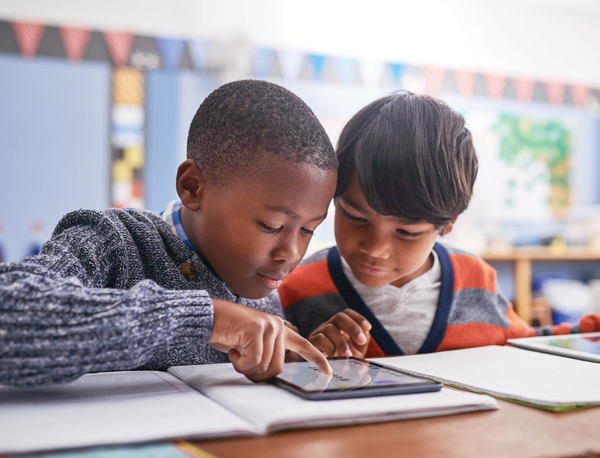

Seemingly, digitalization has permeated every sector of society, including the education sector. It constitutes new technologies as new types of literacies that every human being must acquire to function as a member of any society. These technologies are no longer “just add-ons but occupy the very centre of those forms and practices of communication and representation that are crucial in our new times” (Alhumaid, 2019, 14).

Digital devices such as iPads, tablets, phones, and computers have reconfigured the pedagogic process. The aim of education in the contemporary world has transcended that of a literate to that of a functional society. Dewey rightly posited that:

…a mobile and changing society that is full of channels for the distribution of a change occurring anywhere must see to it that its members are educated to personal initiative and adaptability. Otherwise, they will be overwhelmed by the changes in which they are caught and whose significance or connections they do not perceive (357).

Though Dewey raises concerns about the potency of education requiring its users to be receptive to the dynamic events as they unfold in a changing world, something tenable is the discord that comes with the changing societies. The reality of being a global phenomenon does not spare the education sector since classroom pedagogies, skills, and discussions are now centred on digitalization, globalization, and virtual interactions, among other related terminologies.

The emergence of technology could be described as an infiltrating force that has contributed significantly to the growth of nations and individuals; however, I argue in this article that these evolving technologies also have their shortcomings. Freire seems to be in the right direction in that humanization is that of humankind’s central problem that takes an inescapable concern (Freire, 1996). The relationships between humans and machines or technologies are shifting, and the differences are becoming blurred. Students are now confronted with the reality of digitizing texts at the expense of printed texts.

The problems I noted are that several discussions in the literature solely aim at how digitalization can be infused into the teaching-learning process with no epistemic or ethical considerations of technology on human subjects, and (2) how the field of education is widely subsumed in the perspective that technology is mostly positive and beneficial to the students, teachers, and pedagogical practice, a case of technophilia. The ultimate goal of the global education agenda is to ensure an equitable and inclusive learning society where students can flourish. However, while the imports of technologies in education may be unavoidable in the 21st century, I argue that there are epistemic and ethical implications that may be overlooked in the literature.

The education system, being peculiarly a human affair, is now witnessing a form of aloneness or withdrawal of the young ones from society’s web of interaction, into which education is meant to induct them. More so, the teacher-student relationship could be seriously threatened if machines in the mode of artificial intelligence are overly dependent on them as aids. Teachers may be forced to act as content designers and not as content creators. Technology could also create more barriers and inequalities, increase isolation, dehumanize individuals, and distort social relations. The education system, without some precautions as regards the inclusion of technologies, might jettison the normative role of education in instilling essential values in the learners. This, ultimately, might reduce human-human or teacher-student contact and, inevitably, lead to a standardization of education that was once frowned upon.

The acceptance of technologies might jeopardize and pose several risks to the efforts of educators and policymakers. The risk of over-standardization may also become a quagmire when technologies become distant, costly, and less accountable and responsive in the educational system. It is incontestable that global culture may transcend the education system to a state where robots act as humans – a state of blinded giants, where people have no direction and act as objects. The growing pace at which the inclusion of technologies becomes the new normal in the present education system therefore calls for an interrogation, especially in its global promotion, bearing in mind that education is, after all, a human affair.

REFERENCES

Alhumaid, K. (2019). Four ways technology has negatively changed education. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 9(4), 10.

Dakar Framework for Action. (2000). Education for all: Meeting our collective commitments.

Dewey, J. (2013). The school and society and the child and the curriculum. University of Chicago Press. Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). New York: Continuum, 356, 357-358.

Global Campaign for Education. About education for all.

Murunga, G. (2019). Impact of an educated person in the society.

Williams, D., & Ginsburg, M. (2013). Educating all to struggle for social change and transformation: Introduction to case studies of critical praxis. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 15(2).

Ikeoluwapo B. Baruwa holds a BEd in Adult Education and Political Science, and MEd in Philosophy of Education from the University of Ibadan. With the reality that inclusive education evokes positive influences on the experiences of a learner as a being qua being, and the unceasing commitment to teaching, research, and community service globally, Ikeoluwapo has been involved in a series of letters on education. Ikeoluwapo’s research interrogates the points of intersection of philosophies and policies as they relate to the promotion of Education for All (EFA).